A Practical Guide to Comic Storyboarding

Have you ever opened a comic and, even though the images are just still pictures, felt like you could hear the characters talk, feel the impact of a fight, or be struck by a single emotion?

The moments that make your heart race or stop you in your tracks usually don't come from flashy drawing alone. They come from the magic hidden in the storyboard.

The storyboard is the comic's skeleton. It's the story's breath. It decides how readers see your story. From switching angles and controlling pace to building emotion, each panel quietly guides the reader's eyes and feelings.

Unfortunately, many beginning comic artists spend most of their time on drawing skills and ignore the importance of storyboarding. They might draw beautiful characters, but the story feels stiff and flat. Or they might have a great plot idea but get stuck at the storyboard stage and can't get readers into the story.

If you've been bothered by these problems, this article might be a quick, practical guide to help you get started with storyboards.

In this article, you will learn:

- Storyboard vs. Comic Storyboard

- Storyboard vs. Comic Storyboard: What's the Difference?

- Comic Storyboard Basics

- Conclusion

Storyboard vs. Comic Storyboard

The word "storyboard" comes from film. It's a chart used before shooting or animating. It breaks a sequence into shots and shows how each shot will move. Storyboards usually note camera moves, shot length, dialogue, and special effects.

Because modern comics share a lot with film, the term has moved into comics, too. In Japan, this step is called a "name."

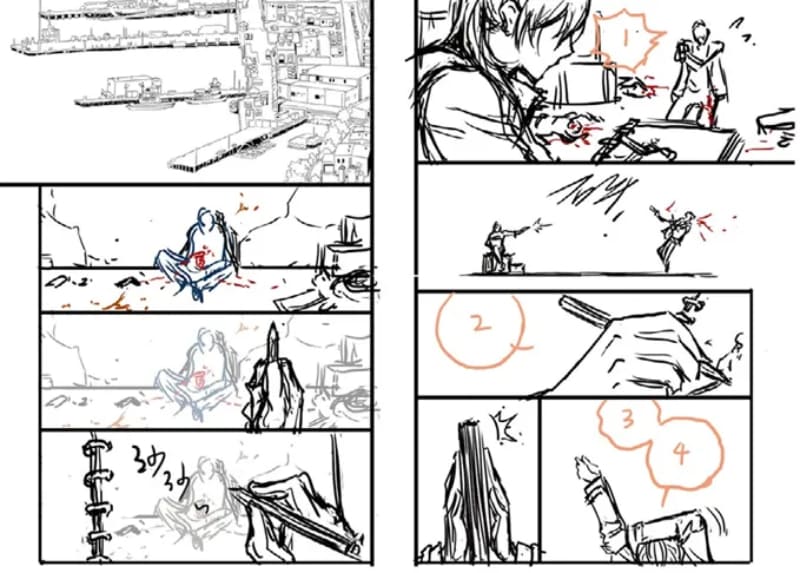

A comic storyboard arranges panels by page or strip. Each panel is sketched roughly to summarize and plan the image. Its job is to show the story's flow and the meaning of each picture.

Storyboard vs. Comic Storyboard: What's the Difference?

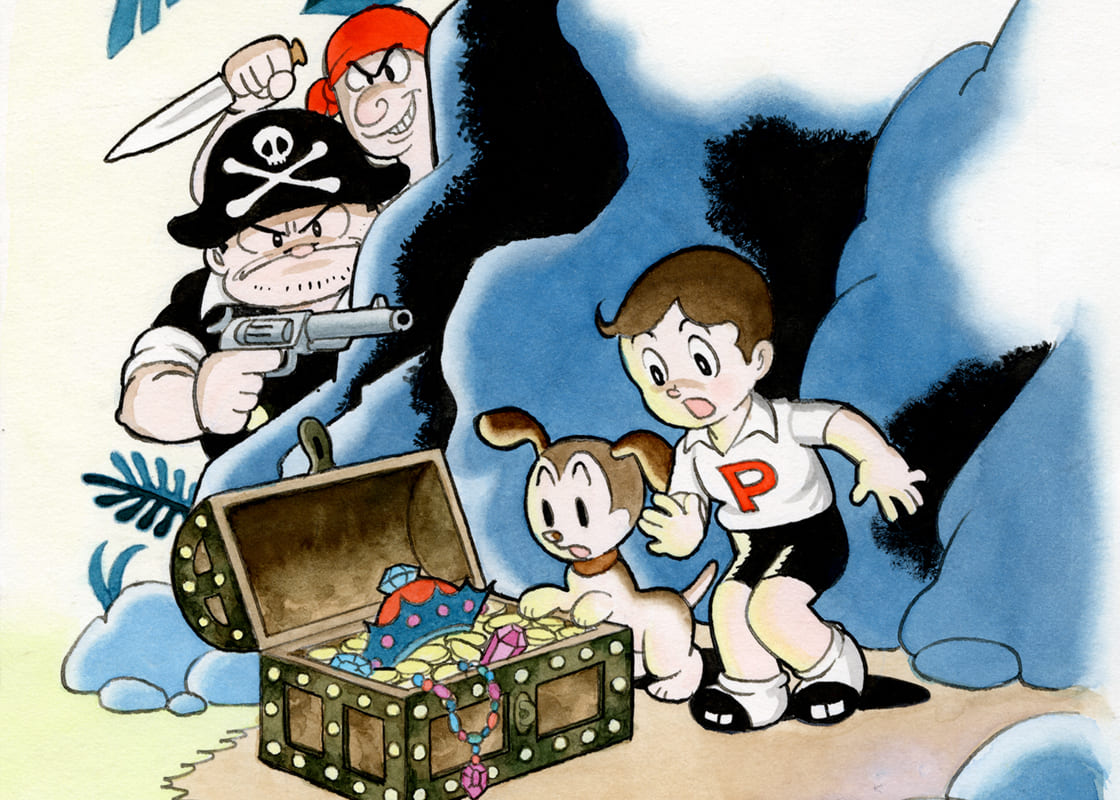

The breakthrough for modern Japanese manga came when Osamu Tezuka mixed film techniques into comics. His work New Treasure Island built on older comics and added cinematic ways of telling a story.

Comic storyboards and film storyboards share a lot. They both use narrative flow, shot language, framing, and camera positions. But they also differ because they serve different media.

Film and TV are made of continuous images that change one after another. Each image the audience sees is a fixed-size frame. Most films show 24 frames per second. When frames play in order, our eyes fill in the motion. So film storyboards are continuous and use fixed sizes.

Comics, however, are organized by page (or by screen for vertical webcomics). A reader takes in one page at a time. That page can have a single panel or many panels in sequence. Readers follow the page in a set order — usually left-to-right, top-to-bottom in Western comics, and right-to-left in Japanese manga.

Within a page, panels can be any shape or size as long as they fit the page. Artists size panels to match the amount of information. Big panels carry more detail. Small panels carry less.

So comic storyboards have a kind of continuity, but they don't need full, frame-by-frame flow. Panel sizes are flexible, and panels can even spill outside their borders. That gives comics more freedom than film storyboards.

Comic Storyboard Basics

1. Panels and Panel Spacing

Whether you're working with page comics (traditional pages) or vertical webcomics (scrolling strips), they're built from a series of panels arranged in a set order.

So the panel is the basic building block. The space between panels — the gutter — matters a lot because it affects the comic's reading rhythm.

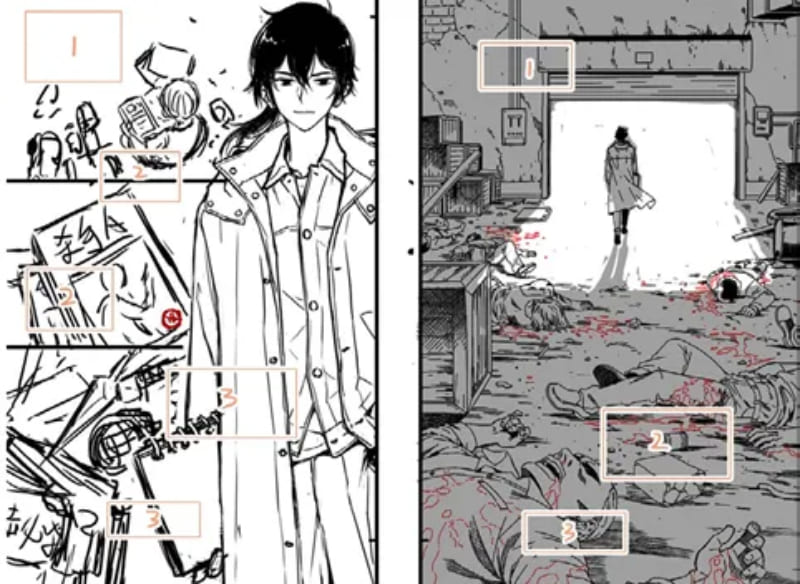

To make pages easier to read, page comics usually have wider gaps between panels vertically and slightly narrower gaps horizontally. That change in spacing gives readers a different sense of time.

Generally, the larger vertical gap makes the order of events feel stronger — one thing clearly happens after another. The smaller horizontal gap makes the two panels feel more like they're happening at the same time.

For example, think about a typical confession-of-love scene.

Vertical Gap

Horizontal Gap

2. Camera Angles

When you make a comic, imagine a camera filming everything your characters do. A camera angle is the angle between that imaginary camera and the character.

There are three common camera angles: eye level, high angle, and low angle.

(1) Eye Level

Eye level is the same height as a normal human view. It's the most common angle in film and comics. This angle feels natural and gives a face-to-face, easy-to-relate feeling.

Because it's so common, it's not the best choice when you want to show extreme emotions or unusual moments. It's usually used for everyday scenes and character introductions.

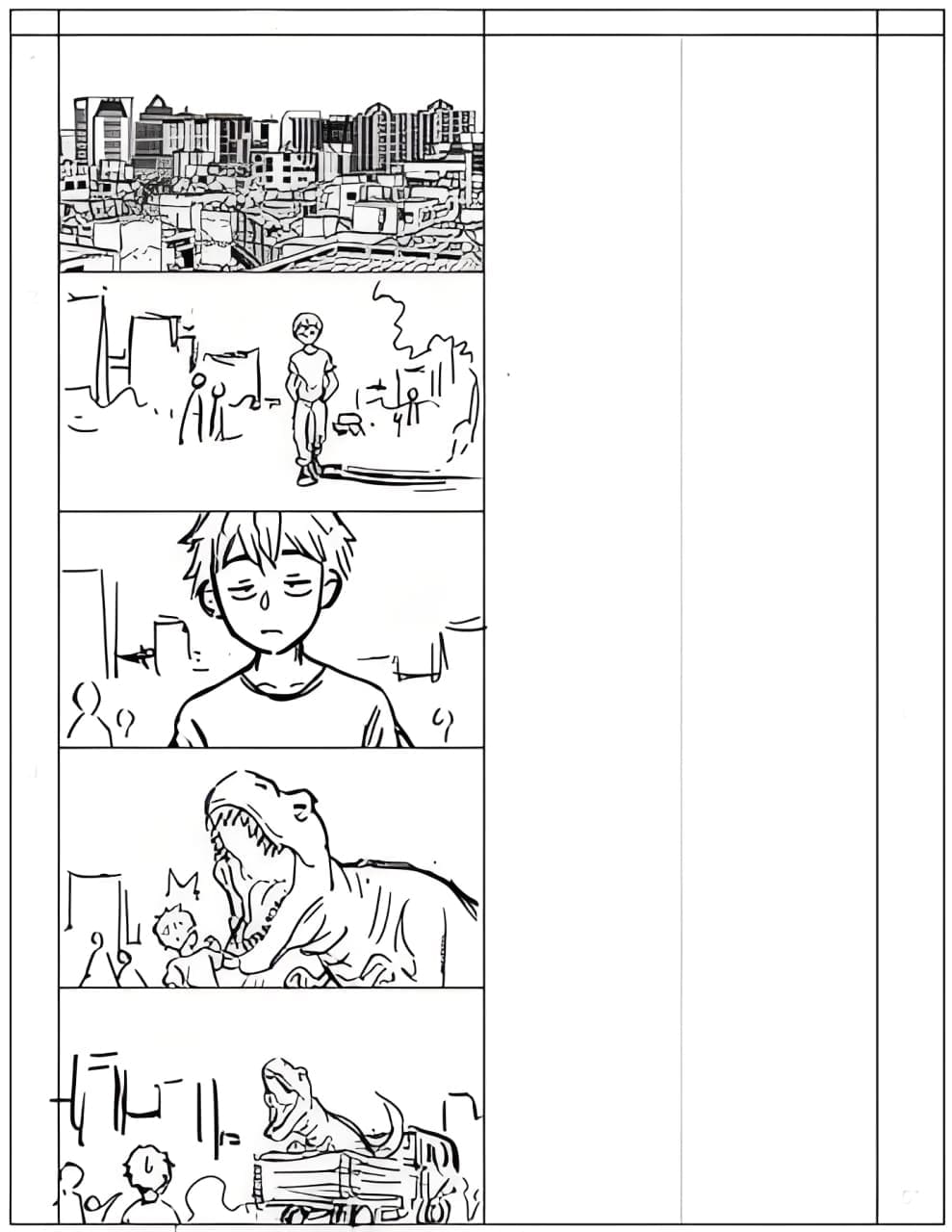

(2) High Angle (from Above)

A high angle looks down on the subject. It's sometimes called a "God's-eye" view. This angle puts the reader in an observer role, so it's less immersive.

But it shows the whole scene well. Use it to explain where characters are, how they move, and how they relate to each other.

It can also make a character look small, lonely, or defeated.

(3) Low Angle (from Below)

A low angle looks up at the subject. It creates a strong sense of presence and can feel oppressive.

Use it to make big things or villains feel powerful. It also works well for horror or suspense.

3. Sound Effects and Other Effect Text

Sound effects are a very important tool in comics. They can stress how a line is said, show a character's inner thought, or act like a short narrator. They also stand in for animal noises, nature sounds, and background audio.

There are other effect words too. These help show small movements or details that are hard to draw clearly.

Sound effects play a special role between words and art. Besides giving sound, they often become part of the panel's layout. They help balance light and dark areas on the page.

A quick rule for color and contrast: if a panel is mostly dark, use white lettering for the sound. If a panel is mostly light, use black lettering. If light and dark are balanced, you can try colored lettering.

These are not strict rules. Use sound effects freely and get creative. Just don't let them steal the scene or confuse the reader.

Conclusion

To become a great comic artist, drawing strong storyboards is the first step. Solid storyboard skills let you convey emotions that connect with readers.

Comic artists often sketch lots of storyboards and thumbnails. A tool that speeds up your workflow can make a big difference. That's why we want to recommend TourBox — a creative controller many artists and comic creators love.

You can map your favorite tools and shortcuts to TourBox's physical knobs and buttons. TourBox's built-in algorithm also opens up more ways to work. Like using a game controller to play a game, TourBox makes creating faster and more enjoyable.

Check our Digital Painting page to learn more about what TourBox can do. If you like working on an iPad, you might also like the TourBox Elite Plus — it gives you a fresh, smooth experience on both PC and iPad.